Split down the middle…

The logging railroads of continental north western America hold a strange draw for me, having neither visited them nor experienced them through museums. It’s been passed on to me second hand…

My Dad, who throughout my impressionable youth was quietly interested in them would describe their distinctive locomotives and individual character when asked ‘what’s that funny looking engine’. Earlier this year a dive down the Canfor rabbit hole generated a pair of Canadian SW1200RS in N scale, why N scale? Well rather than cover that all again take a look at the series of posts on the subject, in fact this could be seen as a natural progression from that exploration, I digress…

|

| Western Forest Products, Camp A reload. Chris Medland photo (https://flic.kr/p/M7Gu9j) |

You only "digress" because we're talking. I worry that's the evidence of my naturally curious, follow every rabbit, way of thinking. Here, where I'm writing this, it's so easy to think of places in the woods, in the hills, where logging happens because it's in those same woods where we hike and explore. Places where you breath the woods and their effect is so much that is permeates your soul. It might seem funny to open with thoughts of oneness with the woods and then write a blog post about modelling the industry that exists to harvest those same trees. We should think about what we do when we harvest trees and allow that to guide how we use their wood in our work to craft things that are no less filled with life, no less a part of life. Where so many other industries a railroad serves are part of complex processes it's always easy to see how a lumbering operation works; it wears all that process on the surface; there's always a feeling that while serving a need to work safely and professionally the nature of this work invites one to improvise to suit a particular tree or site where we're working. All of this and more seems so individual and the scale of that feels relatable to us as individual modellers looking for a prototype we can connect to as one modeller to one real thing.

Saying that, logging railroads need as much space as traditional railroads (if not more), particularly in the diesel era… on the Englewood system trains were regularly over 50 cars long and mainline operations on Weyerhaeuser systems often ran longer, even the trains from various reloads could be 15-20 cars… say a typical logging car is 45-60ft long, so for arguments sake 15 x 50ft cars need over 1.5m in N, make that 2.65m in H0! Enormous… in a landscape you need to absorb this length, and can consider some scale length reduction (as discussed previously) but if modelling a yard, workshop or reload it is difficult to compress this without completely shattering the impression of reality…

If we were modelling a warehouse district, coal mine, or even something as complex as a refinery or steel mill the industry is always something close to the railway line. The industry might be massive but still a thing we can rationalize into a shelf deep space. Yet, we naturally talk about logging railroads using language like "a railroad in the woods" and that's our challenge. If we're going to do this right, "right" isn't going to be about the track we chose or the engines that pull our trains but building a rich scene. It need not be deep, tall, or high, but whatever we do it has to feel enveloping. It has to feel like we're in the woods. It can't feel like the railroad came first. It has to feel like the railroad is a guest where the trees are--in their space.

|

| CME 684 (Alco C415) in 1981. Photo Blair Kooistra |

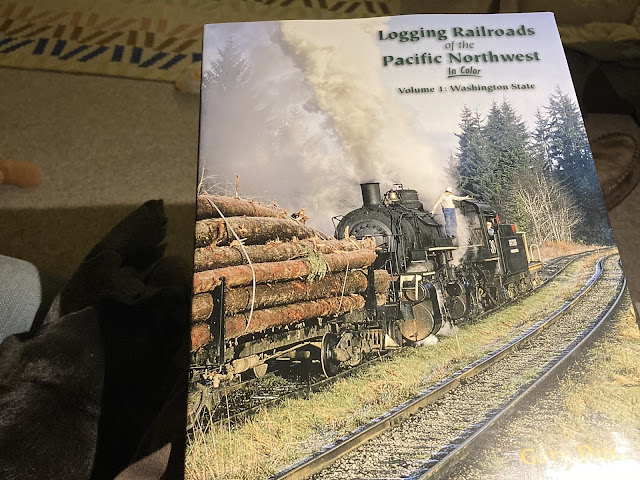

Remember those yellow Fairbanks Morse locomotives? I do too… a Morning Sun book I ordered in the summer finally arrived and contained within its pages are untold stories of inspiration and beatiful trains in wonderful environs… those cab porches, the silver framed cab windows… I started day dreaming of one in H0 from a Walthers model…

“When the train arrived it would run with the empties down one of the open yard and loading tracks, uncouple the power and caboose from the empty train, switch over to the track that the loaded cars were staged on and couple the caboose onto the end of that string of loads. The power would then run round the train and couple onto the loads on which they had tacked the caboose. They were then ready for the the return trip…”

|

| Gary Durr’s wonderful photo album in typical Morning Sun style is full of energy and inspiration, including the quote above. A great read in-front of the fire accompanied by the dog! |

Well in an act of great trans-Atlantic generosity a FM model Chris acquired will be arriving here to be worked over and added to the home fleet. Curiously, even before I learnt of this I had already been day dreaming of a small cameo layout having been playing with the light weight track, pondering initially Pont-y-dulais in the woods, or perhaps the Ruabon Brook arrangement which would give the feel of the end of the yard. I went as far as thinking how, by adding staging, there could be some limited operation in a small space…

Pity there’s not a way to theatrically dispose of the middle of a train because, in a small yard I see some neat “cameo” opportunities for what happens to both ends:

- Receiving and dispatching engines

- Assigning cabooses

- Maintenance cars for the woods

Industrial logging deals in big trees harvested and that means the machines are big and the trains, well, they get long. That train heading to the woods or returning back from the woods might be long but what we do with it is a multiplication of a simple process step. Do we need the whole train to do enough of that to feel like we did it all? How could we truncate this operation to feel like we did enough of it? Like a piece of rope, it's a piece of rope because it has two ends. "Two ends". What if we just focus on the "two ends" of our train and concentrate on the play there and trust that what we show and interact with just keeps carrying on. Like a magician: look at what I'm showing you not what I'm doing.

This is an interesting idea…

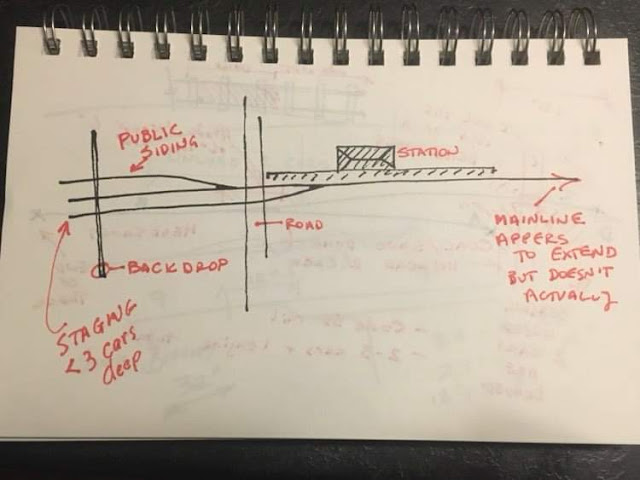

Imagine a shadow box scene with two windows showing each end of the train… the loco would do all the shuffling around at each end, we’d not need to see the middle! I love it! That makes my initial scene (above) just one half the layout…

|

| Sketches in parallel (top James with dog, bottom Chris). |

Where we used to use loads-in-empties-out pairs of industries to overcome the issue of coal loads glued into hopper cars this idea of bisecting the layout to theatrically exclude the middle of a train otherwise too long for a small layout could work similarly well.

There is some real potential in this idea wherein we dispose of the train’s mid-section so we can focus on the parts we want to play with. There’s no reason this couldn’t still be flanked by staging wings on either end. In some ways we’re playing with our perception: how long is that train?

Considering the practical aspects, in particular that ‘hidden train’ and it’s length, there is an inherent advantage in loosing some of it… as I jokingly wrote on my initial sketch this is ‘boring’… In the sense that running around or shuffling a caboose from one end to the other requires a lot of plain running… shortening this distance improves playability, keeping things more operationally interesting. However, a word about what ‘length’ is left, practically it needs to be about the length of one visible ‘window’ so you would only see the front or the back, never both, as it moves through the scene. This needs balancing within the scheme to minimise the ‘blank space’ between the windows…

I can’t help but take things further, the idea of the hidden train even works in an Inglenook style arrangement. What if this was a North American branch station?

Train arrives on mainline and, along the way to here, the crew have been working the train from the front so pull up just short of the public siding’s turnout. There’s two cars in the public siding so they run in and grab those and then back to their own train so they start digging the needed cars out. There’s no work east of here today so they hook the train cars back together again and the use the loop siding to run around the train and grab the coach they’ve been using as a caboose-passenger-mail car and bring it up to move it to this end. With that done they can head back west.

It is interesting to reflect that between us we’ve had elements of this concept previously (see further reading below, and links in the text), however the catalyst was Chris’s comment about ‘the interesting’ bits happening at each end… sometimes it is the casual comment of a good friend that is all we need to take inspiration through to a scheme. A shared energy can generate motivation to turn a scheme into reality, as in this case, more on that soon. In the meantime, I hope this idea permeates and perhaps inspires you to apply the concept to your own model railway? Until next time...

Further reading:

A fascinating concept. I wonder though, if the same could be achieved with a less drastic viewblock? That wing(?) in the middle implies some degree of backscene and attendant exits. Perhaps it would be simpler to place a raised bit of scenery in front of the track, in a continuous scene? Of course, then you have one long scene that can be looked along lengthwise to a much greater extent than the cameos suggested. Maybe a through truss road bridge across the track to break up a longitudinal view, with the abutments splitting the scene in two. Although I suspect that might not fit this particular prototype.

ReplyDeleteTim

That’s an interesting idea too Tim, but I fear that because if the drastic shortening we are talking about here might not be the answer. These windows and separation don’t necessarily mean the backscene wraps around to the front though, however I do feel you probably do need the visual delineator so the mind forgives the compression, seeing them deliberately as two scenes in the same place… does that make sense?

DeleteAh yes, I see. Hmmm, would the centre divider have to be wide enough to completely conceal the locomotive? I suspect if it did, you could suggest length by pausing the loco out of sight, to give the impression it's still getting there from the other end when you change focus on the other scene.

DeleteTim

This concept interrogates our definition of something as simple as "how long is a train?". by describing the train relative to its actions:

DeleteWhen the train is first arriving on scene or exiting the scene we process that movement as one complete train. The practical limitations of the shelf size overall will always prevent this train from being a one-for-one car count but if the train is just long enough during this first or final phase so that the engine and caboose are never in the scene together we lose them as reference points defining the length of the train. We leverage the homogeny of the string of similar freight cars and their repetition as they progress through the scene to build a feeling of the train's length that, hopefully is longer than the train is.

Between entering and leaving are the motions the train goes through while it's on scene and in this case the dramatic break is something that may feel obtrusive until it's experienced. We have breaks like this now already in our typical station to fiddle yard plans so this really is as much like that as it is to the say the American "loads-in empties out" plans. Alternating between scenes is like shifting attention around a stage or gym floor to concentrate on how actors or athletes go about their roles as part of the team. That's there's interplay where the engine breaches the scene (as would the tail of the train) by crossing this hard line from one dimension into the next.

We're often cursing at reality for the amount of space it consumes. I think one of the hobby's unique superpowers is the ability to edit the dimensions of reality to rearrange them to suit our smaller scale spaces. In this divide we can further play with that concept because we can focus on what needs to be in each scene or what carries across each scene. Like the stitching on a good shoe, the train's job is to assemble the scene and provide continuity and context.

Chris