Small Layout Success (Part Three)...

In the first and second part of this series, Chris and I talked about what makes a great small layout and gave some thoughts on composition and colour that can materially impact the success of your own project...

I began by introducing three suggested principles which, to recap, were...

Suggested principes of small layout success:

• Deliberate scene composition

• Consistent colour, both temperature and palette

• Theatrical style viewing window

In the 1990s I inherited my Grandpa's collection of Model Railway Journal, and the story of their 'Inkerman Street' project layout showed an expansive scene presented in a immersive manner where the vertical height of the viewing area was almost totally taken up by a viaduct on the left, and large warehousing along the back, where the depth of scene allowed for a variation in height, where the goods yard textures at the forefront with the mundane and everyday coal wagon provided a foundation somehow for the suburban passenger operation above, all imbued with the dirt and smoke of an inner city location (despite only ever seeing black and white photos)...

|

| MRJ Compendium 2 |

I also recall the Manchester Model Railway Society's 2mm scale magnus opus 'Chee Tor', a truly awesome scenic layout that completely dumbstruck me in it's presentation of the dramatic Peak district limestone landscape. The depth of the scenery here really played with the scale of the trains, to provide something of the scale of the real scene. The layout filled your entire view with a bleak and well observed landscape, a subdued palette of colour, all finished to such a standard and with engaging presentation that it was bound to put the viewer in the scene...

However, whilst these larger layouts conveyed an immersive scene by literally filling your field of view, there wasn't an obvious answer in the smaller scale, smaller footprint layouts. Exhibitions showed us styles from flat baseboards to those with high backscenes including a lighting rig, and everything in between, but all of these fell short of the impact of those large layouts.Even today, we don't have exhibitions here in Canada like the ones James describes. Layouts in our shows remain the domain of the large modular layout. I think this is a contrast of culture that informs our design experience. Layout of the month articles from a British magazine inevitably include a comment by the layout builder discussing their plan to stand in front of, beside, or behind their layout and this creates a sense of connection between viewer, modeller, and layout (1:1:1). The American modular show layout, composed of sections provided by the individual modeller, still encourages a discussion comparing standing in front of the layout or behind it; but the ratio of viewer-modeller-layout is not the same because there's no need to stand by your module so long as someone is near the layout to keep the trains on the track. While there is still someone in front of the layout the opportunities for connection are diluted by the conditions that are derivative of that design. This isn't a conversation about what's inside the box but how does the box itself affect our experience? More than just layout height but if we incorporate a structural lighting valance than the result is a letterbox-like design and how does that horizontally-biased viewing area affect our experience. Does the shape of the front edge of the layout change our relationship of what's inside by modulating our interface, human to thing, with the model railway?

|

| The ‘matchbox’ |

|

| The ‘overlap’ |

I recall a conversation with my Dad over a pint, about the same time as a different style of layout was becoming popular on the exhibition circuit - the cameo... Dad had been a stage carpenter whilst at university and talked about the 'tricks of the trade' and how he had adopted that in his modelling, only creating what you see, not worrying about what you can't, hiding tracks behind scenery and using half relief at the edge of the stage to disguise holes in the back scene... his evocative descriptions of that time in his life helped bring the ideas to life more than just seeing photos in the magazines and the concepts struck a chord with my young mind.

I'll try and define and distill some of that description with elements I've learnt through experience in the intervening twenty odd years...

The defining character of a cameo layout is a theatrical style... a viewing window that allows you to strongly control the view. It’s presentation can be thought of like a stage set with wings hiding the entrance/exits to the scene, disguising where our actors appear and disappear, framing the view in a way where we are encouraged to feel the scene continues beyond the edges, to inquisitively gaze into the scene and fruitlessly try to gaze around the edges, to the beyond. The presentation with a top and bottom pelmet limits how we can view the layout from above, and whether it's even possible to gaze along the tracks, or just across them. As important is the integral lighting, which as the theatre is an opportunity to control another important element 'on stage' highlighting what we want, and disguising what we don't, ensuring our creation is presented at it's best, as we intended.

|

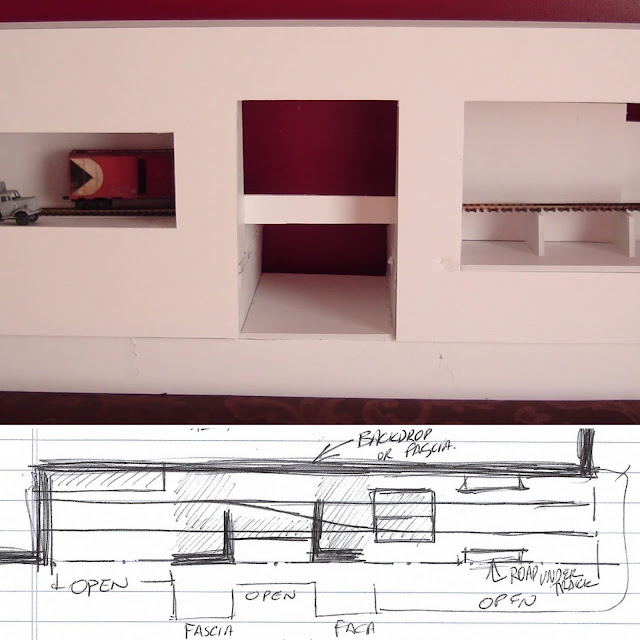

| Mock up and sketches by Chris Mears |

We see a lot of "advice" on how to fit track into a space and as much on how to move trains across the model railway but almost nothing on how to move the viewer around in the space. That's funny isn't it? I mean, the connection point between the human viewer and the model railway scene is a lifeline for the model railway. What matters what happens inside the box if you never get to lift the lid to look inside?

Borrowing from the study of traffic on roads or efficiency within our kitchens we learn that changing the shape of something, changing lighting, or the dimension of a space can alter our relationship with it. A pocket in benchwork might invite the visitor into explore; narrow aisles might discourage people from lingering; a slit in the side wall of our backdrop might tease a curious eye. Lessons from beyond the world of model railroading could be applied to guide the viewer. This isn't about controlling a human but about curating an experience. This isn't a power trip but a question on how to do something with design so that when we share what we've made with someone important to us they get to see it the way we do? Maybe feel it the way we do? It's about asking how to leverage design to enrich that connection potential.

I mentioned my Long Siding as a tool to convert the sense of distance by time lost. Navigation within the scene might be a helpful tool too. If we add obstructions into the scene and weave the path of our trains around these things how does that affect our relationship with distance? If we simply arrange our shelf with all the tall bits at the back and then the trains at the front the scene is too easy to understand. By interpreting it too quickly perhaps it doesn't create a moment long enough to trigger a curiousity about what goes on inside it. It never asks us to climb inside to look around.

In the examples above the placement of buildings creates obstructions you have to look around. You can hear the train working behind those things and you can see it move behind there. You're invited to follow it into the scene to see what it's doing and where it goes. By moving within the space you're exploring its dimensions so instead of your experience being limited to the length of the layout as the only way of defining the space you're adding the depth of the scene or the projection of sight lines to that length and as a sequential experience that initial length of the layout is increased by distance added.

Controlling viewing angles is not only the job of the non scenic framing, as Chris suggests it’s possible to use structures, trees and even the landscape to add what is almost the inverse of traditional modelling, placing things at the front of the layout rather than the back, getting ‘in the way’ on purpose. The engine shed at Pont-y-dulais is perhaps a curious illustration of this as it’s obviously an interesting structure and features some internal detail that encourages further closer viewing and drawing the eye into the scene. However it also serves as a view block, controlling the angle that the left hand end of the layout can be viewed at allowing the crossing and it’s surrounding overgrown bushes to use a fixed photo backdrop that is never viewed from a sub-optimal angle. It also has a third element, it hides the engine momentarily, building anticipation, the waiting time slowing our interaction, adding the opportunity of occurrences to interact, things that increase the time we spend in the space, perhaps even increasing that feeling of space.

|

| The engine shed on Pont-y-dulais, with Hornby B2 Peckett 'Bronwen'. |

Physical stage set presentation, as we call ‘cameo style’ is something I’ve experimented with somewhat accidentally on recent layouts. A few years ago I built East Works and I set the viewing window height at 12”. When viewed at eye level, at close quarters many remarked about the feeling of space (I’d say attributed to previous blogs) however to me this vertical height made me feel somewhat lost in it, it didn't draw me down to the layout scene, it allowed me to float about above the scene looking down rather than into it… contrast this with Pont-y-dulais where I was restricted by the layouts original home, above my work bench (in fact squeezed under East Works) where the letterbox view means the window height is significantly lower yet somehow suits the subject, an overcast day in South Wales as well as tightly controlling how the layout is viewed.

If we can control the height of this aperature it changes the appearance of its length. I created these mockups to really explore extreme examples of playing with this feeling of not only controlling access but also the relationship of horizontal versus vertical dimension...

LETTERBOX LAYOUTS URL>

|

| East Works, set up for viewing at ExpoNG 2019, operated by my friend Harry Dawe. |

As I’ve sat and thought about, distilled my thinking and written my small part in this trilogy the thing that has struck me most is how much I personally love small layouts. The best part of a small layout is the ability to start, create and finish your inspiration in perhaps as little as a few months, certainly within a year. The cost in terms of both space required and £££ are low, however the chance to scratch that itch and model a prototype or photo you’ve wanted to for ages... that’s priceless. When I look back, as with Chris, a lot of my own ‘planned’ schemes fall into the ‘small’ category. Despite planning and building larger longer term projects, I will continue to find a home for small layouts.

I start a lot of layouts that never progress far. That's an embarrasing part of my story but almost every one of them has been atypical of different design. Scrolling back through a thousand posts on Prince Street I see so many examples where I learned something about design that has made helped me understand what I want from the next model railway. I don't understand this idea of a lifetime layout because no life is an unchanging static thing. We should grow. These things we express love toward and give life into will grow with us and mature alongside as part of the collective experience of our life. Years ago during one of our amazing discussions on craft and the human experience Krista casually dropped the phrase "human-centric layout design" on me in her usual effortless style and like her, I chase that phrase as part of my reason for being. Too much of our design places the model railroader in a position of serving the needs of the layout yet what we're building is for us. This hobby is not "cool" like rock'n'roll or really knowing whiskey so its something we do because we need to. So much of our participation in it salves a need from deep within our soul. We should do things that respect the investment of our self we make into what we create so that the experience of doing this was worth it.

These three elements have no hierarchy, each must be considered in turn and the result iterated through a process of conception and evolution during construction. The result will be a layout that delivers on your initial aim: to reference a scene, a prototype, in miniature and evoke the emotional response in yourself, as well as others. That is my measure of small layout success...

This series was something that grew out of a conversation James and I are having. It excites my creative self in ways I can't describe that we're thinking like this and hosting a design conversation like this. As always, if you're still reading this far in I can't thank you enough. Also, if you made it this far what do you think? If this is really human-centric it's about all of us, each of us, you too. What do you think?

Interesting. I have to say that Inkerman St worked better in photos than in the flesh. It was actually very hard for the viewer to get the same perspective. Oddly I was thinking about Chee Tor the other night and why it worked, which was that it recreated a view that you could imagine being from the other side of the valley. I was re-reading Iain Rice's book on cameo layouts last night and found myself wondering if a new orthodoxy has been created that is in danger of becoming a cliche.

ReplyDeleteIt’s interesting you thought it becoming a cliche... I think plonking a layout in a theatrical presentation box without considering these elements may not be successful, and hence less successful cameos may make them feel cliched. I hope Chris and I in our ramblings have helped others guide their way through our approach, and that may help lead to more fulfilling modelling.

DeleteI got a shock at a Warley show one year, not having visited for some time, with the different approaches being explored by European modelers. Some of the ideas weren't totally satisfying, but they were definitely interesting. Things like the use of well thought out forced perspective, scenery projecting outwards and the use of multiple viewpoints. I still think the revolutionary aspect of Albion Yard was that the sceniced offstage area let you look at it from angles that on other layouts would totally destroy the illusion.

DeleteThese are ideas that can be worked in your own ‘at home’ small layout. I hope the structure of these three ‘principles’ can help guide modellers through this process...

DeleteInteresting stuff James... A great blending of artistic flair, with your engineering background. I don't think a lot of engineers are successful at this like you are, and I think even fewer artists can incorporate "engineering" into their artful take on something. Great stuff...

DeleteThanks Jeff, as always very kind - and perhaps, I'd not seen the connection between art and engineering - but I guess the systematic approach applied to the artistic subject is a hint at this background yes. I'm most pleased that people are reading and enjoying. There will be more again in the near future!

DeletePerhaps not "engineering" in its purest sense. But definitely how the structural elements fit together in your designs. This is more "design" than true engineering (you don't really do any maths for what you're doing), but there's engineering principles at work here. (It's worth noting that a lot of "engineering" now days is more designing than not). Anyway... Always enjoy your blog James. It's one of a very few that I follow on a regular basis.

DeleteJohn Armstrong's Creative Layout Design 1978 was the first time I read details of Viewing angles, Eye lines, Noon light, Low light Etc. He even got folk to move onto steps or sit down for different perspectives.

ReplyDeleteJust think of Chee Tor as one big Theatrical Style viewing window of a Roundy-Roundy Layout.

It has two big screen blockers at the front corners, one of which had the Tor around and over it, which forced the viewer to look full depth. Most Roundy-Roundy Layouts treat the sides as a different scene , the Tor made you think there was no side view . ( there was a small cameo box as such, of the Tunnel/Bridge/Tunnel). On any large Layout you have to use the scenery as the framing to stop that Helicopter shot, many times over.

For your Deliberate Scene Composition , I think back to Pre Digital Photography , to save film you set the shot up, it could take ages to get the light and the angles right, your just building those shots in 3D, walking along the layout (it may be only one step) but you may have to lie down to get that shot! That shot may be through the doorway or under the Bridge.

Remember you can spend weeks getting the lighting right, you are painting just as much in light, for an old style Magazine Photographer to turn up with a bank of floods! The light is the Biggest thing that changes in a day , those shadows move, they get fainter and stronger, you can do that on a small layout. I dreamed of ways to have moving cloud shadows chasing across the hills of Chee Tor back then. I could now do it with a Digital Projector and a shadow cloud program. It may take sometime to write with the angles across the layout.

Calvin

Calvin that is a great read, thank you for taking the time to write and build with such an expansive comment! I certainly enjoyed and agreed with a lot of what you mention.

DeleteI was looking at this post, again, because I wanted to see that photo of East Works overall. You've shared photos of the layout before and it looks massive in detailed photos yet, clearly, it was quite small. I'm hooked. That's beautiful.

ReplyDeleteChris

Thanks Chris, it moved on to a new home last week, a good home too, clearing the mental space to start on a new project... https://paxton-road.blogspot.com/2019/10/east-works-at-expong.html

Delete